§0. Introduction

Copy/paste (plain text):

Jason St George. "§0. Introduction" in Next‑Gen Store of Value: Privacy, Proofs, Compute. Version v1.0. /v/1.0/read/part-i/0-introduction/§0. Introduction

Every monetary epoch begins with an argument about what is real. James Dale Davidson and William Rees‑Mogg, in their seminal work The Sovereign Individual, argued that the decentralization of computer networks would erode centralized power, and that governments, in their death throes, would reach for more aggressive tools of control: capital controls, nationalization, outright authoritarianism.

The old guarantees (central banks, broadcast media, credentialed authority) no longer hold their shape under the pressure of digital networks and foundation models. They are under attack, not by a single conspirator, but by the physics of decentralization itself, which dissolves the monopolies that once defined our shared reality.

Marshall McLuhan saw an even deeper shift: the move from print, a one‑to‑many medium that centralizes narrative, to electronic networks, a many‑to‑many mesh that fragments it. A print‑created reality is a centralized reality: he who controls the press, controls the narrative. This underwrote 20th‑century monetary supremacy and global settlement currency backed by a monopoly on violence: the post‑1971 US petrodollar.

In the 20th century, citizens got their singular cultural feed from The New York Times over breakfast, and later their dualistic, pseudo‑antagonistic programming from CNN and Fox News. In the 21st, the internet (many‑to‑many) erodes this centralization of narrative. Take the network formerly known as Twitter: authoritarian regimes that attempt to censor information find it very hard to stop leakage. Within minutes, people with “smart” phones can produce a preponderance of evidence that either supports or invalidates the prevailing story.

But a countervailing force has arrived: AI. The quality of realistic generated content has crossed a critical threshold, approaching the asymptote of believability. Synthetic faces, voices, and scenes now compete with direct sensory experience.

This creates a world wealthy in symbols but poor in anchors: a sea of abstractions with no obvious way back to sensible shores.

So we look for new anchors.

Cypherpunk cryptography is the unifying answer: privacy by default, proof by construction, and compute that only gets paid when anyone can verify it. It replaces authority with protocols and gossip with receipts. In this frame, money is not a promise from a platform; it is what remains when verification is cheap and permission is irrelevant. Cypherpunks don’t ask for integrity; they instrument it. They don’t trust platforms; they price receipts. The triad is that credo made economic: privacy that preserves agency, proofs that travel, and compute that earns only when anyone can verify it.

Bitcoin’s SHA‑256 puzzle was a brilliant bootstrap: it minted digital scarcity by tying consensus to thermodynamic cost. The next stage in the evolution of blockchains keeps what made PoW legitimate (open admission and unpredictable leader election), but swaps the work function so the “lottery ticket” is earned by producing succinct, publicly verifiable receipts of useful compute. Miners don’t win by burning cycles on nonce search; they win by attaching a proof that some market‑demanded computation was done correctly.

A natural anchor workload is matrix multiplication. MatMul‑PoUW constructions make verification asymptotically cheaper than naive production (for example, verification vs. multiplication) while keeping verifier overhead at relative to the best‑known randomized checker. That turns AI’s core primitive into verified FLOPs: a commodity unit anyone can check cheaply. Projects like Nockchain show the zk‑PoW design space operating in the wild (fair‑launch ethos, scope‑minimized “dumbnet,” explicit issuance), illustrating that proof‑carrying work can be wired into consensus without appointing gatekeepers. Keep the lottery; change the work. Make the prize a receipt the public can verify, not heat no one can use.

Operationally, the goal is simple: bind useful work to the hash race without introducing trust.

Two deployable patterns are in scope:

- (A) Hash‑gated useful work. A SHA‑family threshold confers short‑lived eligibility; a block is valid only if it carries a PoUW artifact (e.g., MatMul proof or zk‑proof) seeded by header randomness.

- (B) Proof‑first selection. Miners race to post useful‑work receipts to a mempool; header entropy resolves ties and timing.

Both patterns must prevent precomputation (epoch seeds, commit‑reveal), avoid closed‑hardware dependencies, and expose verifier‑light clients plus dispute/slash routes for junk artifacts.

When blocks routinely carry proofs that clear public SLOs and decentralization telemetry remains healthy (time‑to‑first‑proof, top‑N share, geo/ASN spread), block rewards stop subsidizing waste and start underwriting capacity the world already buys: ZK proving, matrix multiplication, verified inference. That is the philosophical and operational upgrade: a puzzle that mints receipts, not heat, so Privacy, Proofs, and Compute begin to behave like money.

The rest of this Part translates that intuition into claims, contributions, a threat model, and a layered architecture.

0.1 Central Claims

In this thesis we argue:

-

Post‑Bretton Woods money is compliance‑backed, not reserve‑backed. The modern monetary system relies more on surveillance, capital controls, and regulatory force than on convertibility or reserves. When compliance becomes weaponized and asset freezing becomes policy, neutral stores of value become necessary infrastructure, not ideological luxuries.

-

Three cryptographic capacities can function as monetary primitives. Privacy (censorship‑resistant settlement that preserves agency), Proofs (portable attestations of computation and provenance), and Compute (useful work wrapped in succinct guarantees) are scarce capacities the world must continually buy. Each can be engineered to be credibly scarce, permissionless, censorship‑resistant, and cheap to verify.

-

A modular stack can operationalize this triad. We propose four reference applications (private treasury & payroll, media provenance, verified inference, proof/compute procurement) built on twelve primitives, with verification asymmetry and VerifyPrice as the key economic metrics that turn proofs and verified FLOPs into commodities rather than platform IOUs.

-

Verifiable machines (Layer 0) are the precondition. Without open, auditable hardware designs and sampled supply chains, the entire stack devolves to “trust the vendor.” Open hardware is not ornament; it is the base layer that achieves common knowledge of security among mutually distrusting actors.

In the rest of the thesis we make this concrete in modular form. Four reference applications exercise the stack (private treasury & payroll, media provenance & authenticity, verified inference as AI service, and proof/compute procurement), supported by a small toolkit of primitives: a proofs‑as‑a‑library SDK (“PaL”) that compiles claims to proofs, a privacy‑rails kit that executes non‑custodial, refund‑safe settlement over BTC↔ZEC/XMR corridors, a minimal receipt schema (“PIDL”) that turns every proof or settlement into a portable artifact, neutral router logic that keeps useful‑work markets open, and a VerifyPrice observatory that measures how cheap verification really is. Later sections develop these primitives and applications in detail; here we refer to them by name once the context is clear.

The overall thesis is simple: the next reserve asset is not a single object but a triad of verifiable necessities: Privacy, Proofs, and Compute. Treat this triad explicitly as cypherpunk monetary primitives:

- Privacy: the right to hold and move value without chokepoints (to preserve agency).

- Proofs: cryptographic attestations of origin, integrity, identity, or computation (to crystallize truth).

- Compute: useful work (ZK proving, matrix multiplication, verified inference) that applications demand and that blockchains can verify cheaply (to power intelligence).

These are not slogans. They are the cypherpunk stack distilled into assets: what cannot be forged, what no one has to bless, and what everyone can check. They are scarce capacities the world must continually buy because life in a dense, digital civilization requires them. Each has its own economy; together they form a monetary base.

Institutionally, this is not just a design for another chain. It is a research and engineering agenda: a Bell Labs for proof‑of‑useful‑work and the zk economy. Where the original Bell Labs turned Shannon’s information theory into cables, switches, and semiconductors, the mandate here is to turn privacy primitives, zero‑knowledge, and verifiable compute into everyday infrastructure: receipts, rails, and verifiable machines that other people build on without thinking about it. This document is the charter for that lab.

Each primitive is designed to be credibly scarce, permissionless, censorship‑resistant, and cheap to verify. Where gold condensed geology and Bitcoin condensed randomness, this triad condenses the utilities of the information era into assets: things that cannot be faked and do not ask permission, cheap for anyone to verify yet costly to produce or deny.

Networks that supply these at scale will earn a durable store‑of‑value premium because the world must keep buying their utility through every cycle, even (and especially) under financial repression and currency debasement.

0.2 Contributions

This thesis makes four main contributions:

-

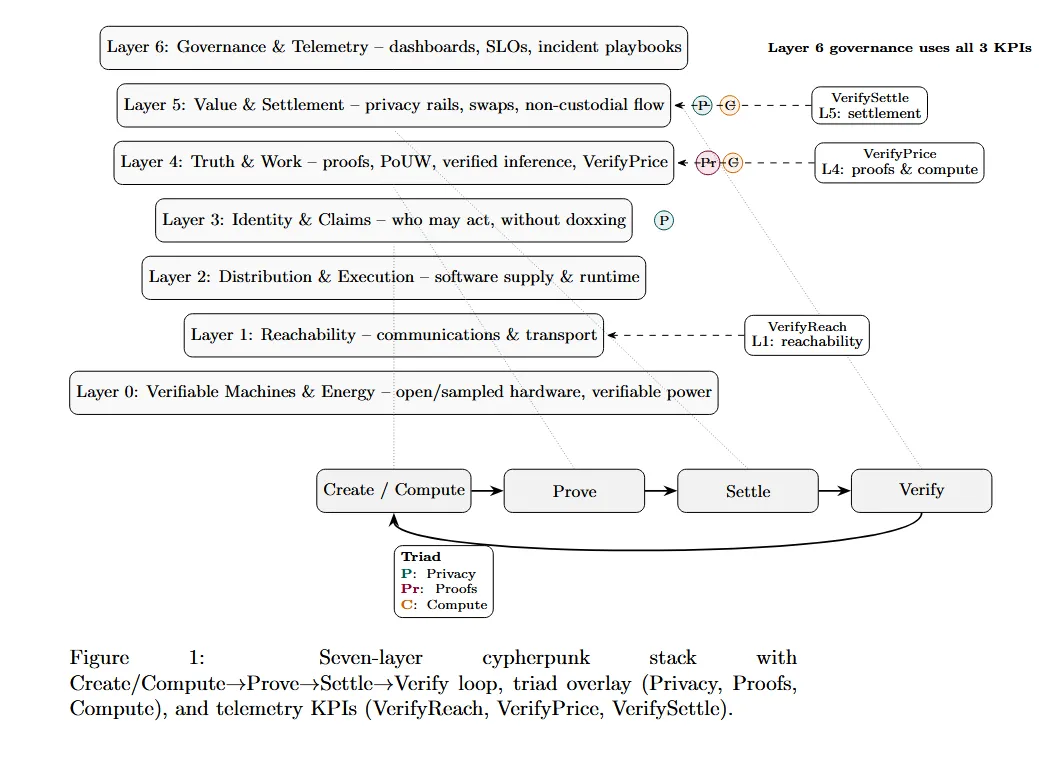

Threat model and layered architecture. We build a threat model that assumes intentional repression rather than benevolence: financial repression (YCC, capital controls), censorship and shutdowns, hardware and identity capture, and platform‑mediated reality. On top of that we propose a seven‑layer “cypherpunk stack”:

- Layer 0: Verifiable Machines & Energy

- Layer 1: Reachability (communications & transport)

- Layer 2: Distribution & Execution (software supply & runtime)

- Layer 3: Identity & Claims (humans and machines without doxxing)

- Layer 4: Truth & Work (proof systems, PoUW, VerifyPrice)

- Layer 5: Value & Settlement (privacy rails, non‑custodial flow)

- Layer 6: Governance & Telemetry (keeping neutrality and resilience measurable)

The rest of the thesis walks this stack from silicon and power up through proofs, settlement, and governance.

-

Economic formalization: verification asymmetry and VerifyPrice. We formalize verification asymmetry as the ratio between verification and production cost for a workload (W), and introduce VerifyPrice (a public KPI vector of p50/p95 verify times, costs, and failure rates) as the hinge that turns proofs and verified FLOPs into commodities rather than platform IOUs. This gives a quantitative basis for treating Privacy, Proofs, and Compute as monetary primitives and for defining “AI money” and “ZK money” as assets backed by verifiable work.

-

Modular stack: four reference applications and twelve primitives. We propose a Create/Compute → Prove → Settle → Verify loop and instantiate it with four reference applications (private treasury & payroll, media provenance & authenticity, verified inference, and proof/compute procurement), built on a reusable kit of primitives. These include a Proofs-as-a-Library SDK (PaL), a Privacy Rails Kit (PRK) for non‑custodial settlement, Proof Interface Definition Language (PIDL) as a minimal receipt schema, MatMul‑PoUW and verified‑inference harnesses, canonical workload registries, multi‑ZK adapters, SLA escrow/slashing, neutral routers, bridge‑safety templates, and a telemetry layer that keeps useful work and neutrality measurable across chains and vendors.

-

Telemetry, governance, and implementation playbook. We extend VerifyPrice into a broader observability regime, including VerifyReach (reachability under censorship) and VerifySettle (settlement success and refund safety), and propose a “no dashboards, no trust” governance posture where protocol changes and incident responses are driven by SLOs and public receipts rather than foundation fiat. We complement this with an adoption curve, an operator/investor checklist for SoV evaluation, and implementation sketches (Layer‑0 hardware, privacy corridors, proof factories, developer SDKs) that make the stack actionable for builders and allocators over the next 12–36 months.

0.3 End-to-End Vignette: The Loop in Action

Before diving into theory, here is a concrete story that walks the Create/Compute → Prove → Settle → Verify loop. This vignette shows how the stack works as a felt reality, not just a framework.

Scenario: A Company Under Capital Controls Runs Payroll

TechCo is a software company with employees in three countries. Local banks are increasingly unreliable: one jurisdiction has imposed capital controls, another requires intrusive reporting, and exchange rates are manipulated. TechCo’s CFO wants to pay staff in a stable, private, auditable way—without exposing salary data to competitors or governments, but with the ability to prove to auditors that payroll was run correctly.

Step 1: Create (Intent)

The CFO opens TechCo’s treasury dashboard (built on PRK, the Privacy Rails Kit). She creates a payroll batch:

- 47 employees

- Total: 142,000 USD-equivalent in Work Credits

- Policy: “Salaries are private; aggregate spend is auditable; individual amounts disclosed only with employee consent.”

The dashboard compiles this into a claim: “Pay these 47 recipients the specified amounts, under this policy, by end-of-day Friday.”

Step 2: Prove (Compliance + Privacy)

The claim is sent to PaL (Proofs-as-a-Library). PaL compiles it into two proofs:

-

Compliance proof: A ZK proof that the batch satisfies TechCo’s internal policy (aggregate under budget, recipients are on the approved list, no single payment exceeds threshold). This proof reveals nothing about individual amounts or identities—only that the rules were followed.

-

Integrity proof: A hash commitment binding the full payroll data. This hash is stored on-chain; the actual data stays encrypted in TechCo’s vault.

Both proofs are packaged into a PIDL receipt: claim hash, proof hashes, workload ID, SLA tier, timestamps, and a prover signature.

VerifyPrice checkpoint: The compliance proof took 2.3 seconds and cost p_{95,t} \leq 5\text{s}p_{95,c} \leq 0.01$ USD).

Step 3: Settle (Private Execution)

With proofs in hand, PRK executes the payroll:

-

For employees in the capital-controlled jurisdiction: atomic swap via BTC↔XMR corridor. TechCo’s BTC is swapped for XMR, which is sent to employee wallets. The corridor is non-custodial; if anything fails, funds return to TechCo (refund-safe).

-

For employees elsewhere: direct settlement over a shielded pool (e.g., Zcash). Each payment is encrypted; only the recipient and TechCo (via viewing keys) can see the details.

VerifySettle checkpoint:

- Swap success rate: 98% (2 retries due to network latency, both succeeded).

- Refund safety: 100% (all potential failures would have returned funds).

- Time to finality: median 4 minutes, p95 11 minutes.

- Anonymity set: 12,000+ active notes in the shielded pool.

Step 4: Verify (Audit Trail)

After settlement, the following are publicly verifiable:

- On-chain: The PIDL receipt exists, the proofs verify, the aggregate amount was transferred at the specified time.

- By TechCo’s auditors: Using viewing keys, auditors can see the full breakdown (who got paid how much) and confirm it matches the compliance proof.

- By employees: Each employee can verify their own payment arrived, using their private key.

- By anyone: The compliance proof demonstrates policy was followed, without revealing any private data.

What the adversary sees:

- A capital-controls regulator in Country A sees: “TechCo moved some BTC into an XMR corridor.” They cannot see amounts, recipients, or purposes—unless TechCo chooses to disclose.

- A competitor monitoring the blockchain sees: “Some shielded transactions occurred.” They learn nothing about TechCo’s payroll structure or employee compensation.

- A hacker who compromises a single employee’s device sees: that employee’s payment. They cannot reconstruct the full payroll or identify other employees.

What TechCo gains:

- Privacy: Payroll data is not exposed to competitors, governments, or hackers by default.

- Compliance: Auditors get cryptographic proof that policy was followed, without needing to trust TechCo’s word.

- Resilience: Even if banks freeze accounts or exchanges delist, the privacy corridor remains operational.

- Receipts: Every step produced a verifiable artifact (PIDL receipts, proofs) that can be archived, audited, or used in disputes.

The loop in summary:

| Stage | What Happens | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Create | CFO defines intent + policy | Claim |

| Prove | PaL compiles compliance + integrity proofs | PIDL receipt |

| Settle | PRK executes via privacy corridors | Value transferred |

| Verify | Anyone can check proofs; auditors use viewing keys | Audit trail |

This is lawful privacy: default-private, optional-disclosure, with receipts that anyone can verify. The triad (Privacy for settlement, Proofs for compliance, Compute for proof generation) works together to make the flow possible.

Variation: Media Provenance

The same loop applies to a journalist publishing a video:

- Create: Camera with secure element captures footage, emitting a signed provenance attestation (device ID, timestamp, geolocation hash).

- Prove: Edit suite issues proofs of each transformation (crop, color grade, caption). Each edit is a new PIDL receipt referencing the parent.

- Settle: (Optional) If the video is monetized, payment flows over privacy rails to the creator, with receipts linking payment to provenance.

- Verify: Any viewer or platform can verify the chain: “This video originated from camera X at time T, was edited as follows, and has not been tampered with since.” Deepfake detectors can check against registered provenances.

Platforms that strip metadata cannot strip the on-chain PIDL receipt. The proof persists even if the platform delists the content.

These vignettes are not hypothetical futures; they are the concrete scenarios the rest of this thesis is engineered to support. The stack exists to make these flows cheap, verifiable, and non-custodial under adversarial conditions.

Tip: hover a heading to reveal its permalink symbol for copying.