§2. The World Forces New Monetary Primitives

Copy/paste (plain text):

Jason St George. "§2. The World Forces New Monetary Primitives" in Next‑Gen Store of Value: Privacy, Proofs, Compute. Version v1.0. /v/1.0/read/part-i/2-world-forces-new-monetary-primitives/§2. The world forces new monetary primitives

2.1 Macro playbook: debt → repression → flight to neutrality and quality

Total global debt (private + public) according to the IMF’s latest Global Debt Database now sits at a roughly ~2.4x multiple of world GDP, with some economies (such as Japan) exceeding 400% of GDP when public and private debt are combined. Standard scenarios from multilateral institutions point to global public debt approaching ~100% of GDP by decade‑end, after already exceeding $100 trillion in the mid‑2020s.

Historically, such overhangs are closed via financial repression: inflation plus regulation that imposes negative real returns, including overt capital controls and captive‑balance‑sheet rules, pushing savers toward neutral, censorship‑resistant rails. “Voting with your feet” is harder when the exits are policed at gunpoint.

Sidebar: The Bondholder Kill Box (How Repression Works)

-

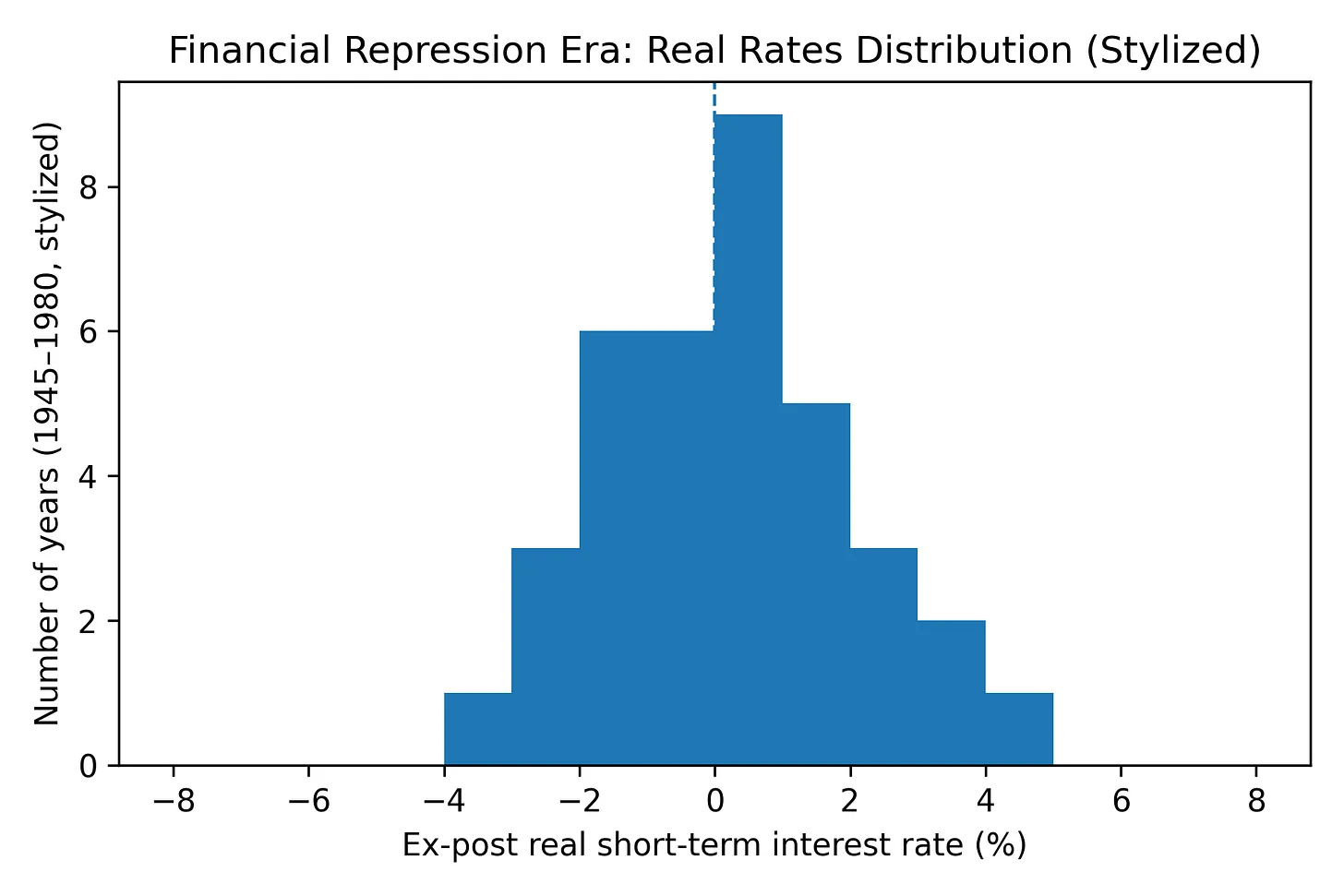

Definition. Financial repression is a stealth tax on savings: cap nominal rates, let inflation run, and force captive balance sheets to hold the paper. The result is systematically negative real returns for depositors and bondholders; an engineered wealth transfer to the sovereign. In the post‑WWII advanced economies, real rates were negative in roughly half the years from 1945–1980, and the “liquidation tax” (interest‑expense savings on the public debt) averaged on the order of 1–5% of GDP per year.

-

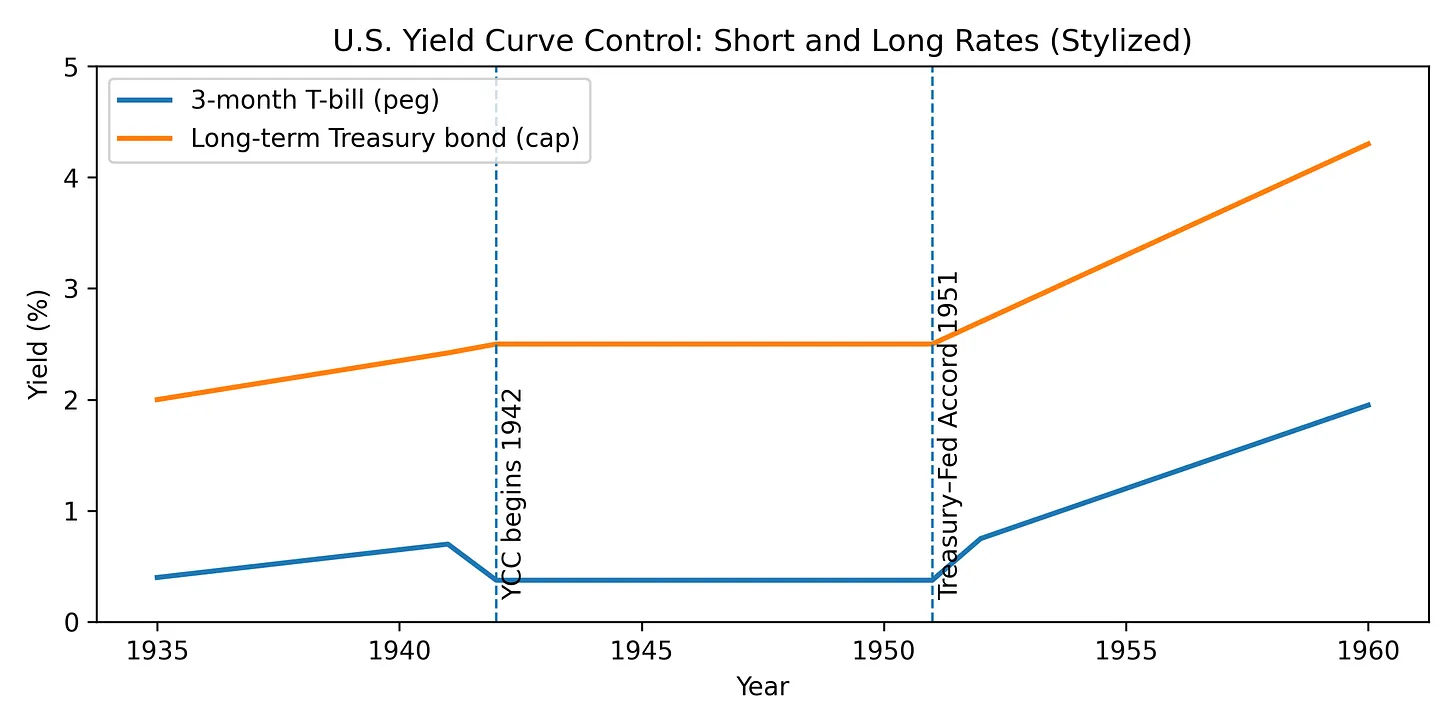

How the cap is enforced. Overt or implicit yield‑curve control (YCC), administered rate ceilings, capital/liquidity rules that force government paper into banks, insurers, pensions, and collateral boxes, plus capital controls to slow leakage. In the U.S. WWII episode, the Fed capped T‑bills at 3/8% and long bonds at 2½% until the 1951 Accord; when the cap ended, long‑duration holders took capital losses as yields normalized.

-

Why now. With global debt at several times world GDP, public debt ratios trending toward ~100% of GDP by decade‑end, and interest costs compounding, repression is arithmetically attractive to policymakers versus explicit default or politically costly austerity.

Two equations every saver should know:

-

Repression wedge (real carry):

If () and inflation (), the real return is per year.

-

Duration burn (when the peg breaks):

For a bond with duration (), a yield move () produces a price move ().

A 10‑year with () takes about on a +300 bps repricing.

A worked example: three years at real/yr is real loss compounded; then a +300 bps jump deals another price loss, roughly cumulative in purchasing‑power terms. The design is deliberate: bleed bondholders while buying time for the sovereign balance sheet.

2.2 The repression playbook, then and now

Figure 3: U.S. Treasury bill peg and long-bond cap under WWII-era yield-curve control (stylized). Peg at on bills, cap at 2½% on long bonds; dashed line marks the 1951 Treasury–Fed Accord. Source: Rose (2021), Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Figure 4: Stylized distribution of ex-post real short-term interest rates in advanced economies, 1945–1980. Real rates are negative in roughly half the years, consistent with Reinhart & Sbrancia’s estimates of the financial-repression era.

Figure 4: Stylized distribution of ex-post real short-term interest rates in advanced economies, 1945–1980. Real rates are negative in roughly half the years, consistent with Reinhart & Sbrancia’s estimates of the financial-repression era.

The lesson is simple: post‑Bretton‑Woods money is upheld more by regulation, violence (or its threat), and surveillance than by reserves. When repression becomes the spread, capital quietly rotates to neutral, bearer‑like rails. We are already seeing a partial recollateralization of the financial system with gold following events like the seizure of Russia’s reserves in early 2022, and a visible rotation of some marginal liquidity toward privacy‑preserving assets such as Zcash (ZEC) and Monero (XMR).

If “safe” nominal assets become de facto taxes on savings, rational capital routes (not protests) to assets whose issuance cannot be decreed and whose verification is cheap and public.

In that environment, a credible store of value must:

- Avoid being a duration instrument whose real return can be pinned negative by policy; and

- Live on rails that cannot easily be gated by a single jurisdiction.

This is where the triad enters:

- Privacy as an anti‑seizure hull that makes savings bearer‑like again.

- Proofs as cheap public verification that replaces platform vouching.

- Compute as a non‑coupon revenue base whose clearing price floats with nominal budgets rather than being pegged by decree.

Each primitive is designed to remain neutral and verifiable even when traditional financial infrastructure is weaponized.

Enter social network technology.

2.3 Social: the web’s trust default has flipped

The same technological forces reshaping money are also reshaping trust.

The web used to borrow its epistemic norms from broadcast: seeing was believing, and the job of editors was to gate what got seen. Deepfakes and generative models invert that. AI systems can now synthesize faces, voices, and scenes that are indistinguishable from genuine footage to lay observers. Exposure itself doesn’t inoculate people; survey data across multiple countries suggests prior exposure to deepfakes can actually increase susceptibility to misinformation.

In parallel, we get the liar’s dividend: once everyone knows deepfakes are possible, any inconvenient real video can be dismissed as fake. The result is a crisis of knowing, not just a rise in error rates.

This isn’t entirely new (authoritarians have been editing history since Stalin airbrushed Trotsky out of photos), but the cost curve and scale have changed. Deepfake tools now let anyone with a laptop fabricate a leader conceding an election, a riot that never happened, or “footage” of a historical event that subtly rewrites who was present and who was not. The fear is not just short‑term hoaxes; it is revisionist history at machine speed, where archives, livestreams, and “receipts” themselves become contestable. In that world, the substrate of trust shifts from memory (“I saw the clip”) to mechanism (“I can verify how this artifact came to be”).

At the same time, the feeds themselves are no longer obviously “neutral pipes.” Investigations and hearings around government–platform coordination have documented extensive relationships between agencies, NGOs, and major platforms for content moderation in the name of combating misinformation and foreign influence. Whether one views this as necessary harm reduction or problematic overreach, the empirical point stands: the old story that your feed is simply “what’s popular” no longer survives contact with the evidence. What you see (and don’t see) is the result of political, institutional, and algorithmic priors you don’t control.

Content authentication standards such as C2PA and watermarking prototypes exist on paper, but real‑world implementations are voluntary, inconsistent, and often invisible to end‑users. Tests across major platforms such as the Washington Post’s 2025 C2PA test show provenance metadata being stripped in transit, and the few disclosures that do survive are buried in UI that most users never touch.

In other words, the trust default has flipped. The practical baseline for online media is now “untrusted unless proven,” and the “proven” part cannot safely be left to platform labels or government‑platform partnerships. Platform UX is inconsistent; cryptographic provenance and computation proofs are the scalable, cross‑platform backstops.

In a SoV context, this matters because monetary systems sit on top of communication systems: if claims about ownership, origin, and behavior are cheap to fake and expensive to audit, then both money and memory become soft targets. Anchoring value in receipts that anyone can verify, rather than narratives that someone must vouch for, is the only stable equilibrium.

Recent work constructs PoUW for arbitrary matrix multiplication with verification that is asymptotically cheaper than production (e.g., verify vs. produce; “” denotes a constant‑factor overhead relative to the best known verification baseline). Matrix multiplication is the operation that bottlenecks modern AI. This is the asymmetry PoW always needed: hard to produce, cheap to check.

When verification is very cheap relative to production, honesty becomes a market equilibrium and commodities emerge (standardized proofs, verified FLOPs) that can be priced, saved, and eventually used as collateral and stores of value.

Tip: hover a heading to reveal its permalink symbol for copying.